FREQUENTLY ANSWERED QUESTIONS

1. “This is just another angry atheist film.”

Nope, it actually has a bunch of Christian PhD biblical scholars in it. They teach at leading biblical colleges and universities. Google them if you don’t believe us. We included them in the film to demonstrate that the ideas put forward in the film are mainstream biblical scholarship.

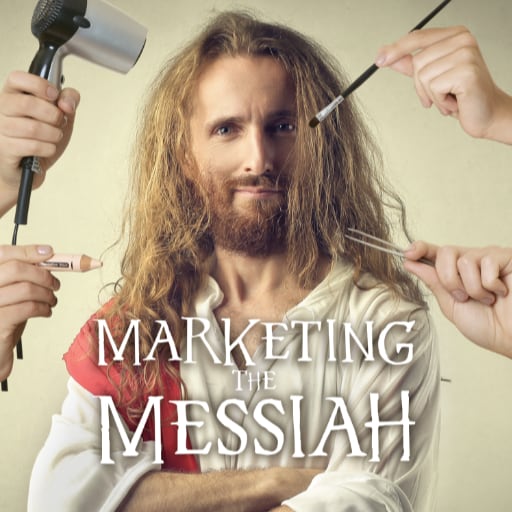

2. “The poster is offensive.”

Why? Because Jesus is smiling? There’s plenty of Christian art where he’s smiling. Or is it because he’s getting his hair done? That’s what worries you? Do you think he never got a haircut or had his beard trimmed?

3. “The title is offensive.”

Why? Because we’re suggesting the concept of a Jewish messiah was changed and then marketed to Gentiles? Well that’s obviously what happened. If that’s offensive, take it up with Paul. He’s the one who did it, not me.

For people who don’t think “marketing” existed back in ancient times, you’re probably thinking about modern forms of marketing. But marketing, eg word of mouth promotion, is as old as humanity. In ancient Rome products and services were marketing constantly, via word of mouth, graffiti, coinage, statues, buildings, events and the written word. Christianity was marketed initially via word of mouth, with the disciples evangelising all over the empire, and then the written word, with the letters and books that evenutally became the New Testament (not to mention the works that didn’t make it into the NT).

4. “This film is mocking God / Jesus / Christians.”

Nope, it actually has a bunch of Christian PhD biblical scholars in it talking about the bible and early Christianity. If you think talking honestly about the history of Christianity is somehow mocking it, then that says more about you than it does about the film.

5. “Why don’t you make a film about Islam?”

Because I was raised a Christian, live in a predominantly Christian country, know very little about Islam, and because Christianity is the biggest religion in the world, so it’s the one I’m most interested in. By the way, I know the reason you suggest Islam as a topic is because you wish violence to happen to me. I’m sure Jesus is really impressed with you.

6. “You should change <see one of the above things> if you want me / Christians to watch it.”

Look, we always knew there would be some Christians like you who would get their noses out of joint over one of the above things. We have tried to make a secular history documentary about early Christianity that would be factual and entertaining for both Christians and non-believers. But we’ve been around long enough to know you can’t please everyone and it’s a waste of time trying. So if you can’t get past one of the above five things, then that’s okay – don’t watch the film. You probably wouldn’t like it anyway. It’s not for you. It’s for Christians who aren’t so sensitive and have a sense of humour. Their faith isn’t so easily threatened.

7. “These so-called ‘experts’ don’t know what they are talking about / aren't true Christians.”

Nearly everyone in our film has a PhD in either New Testament or Ancient History. They have devoted their lives to studying this subject. If you think you or your pastor knows more about the history of early Christianity, then please contact us and we’ll invite you and/or your chosen expert onto our Marketing The Messiah podcast to tell us why our scholars are wrong. When you think you know better than the majority of experts in a particular field, you are either a) an expert with a PhD yourself or b) suffering from the Dunning-Kruger effect.

And half of the scholars in the film are Christians. Some are even pastors in their churches. I’ve had some people suggest that they still aren’t *real* Christians, because apparently if you are honest about the history of Christianity, then you can’t be a real Christian. Who gets to decide who is a real Christian and who isn’t?

8. "Luke’s genealogy traces Jesus lineage from King David through Mary.”

That’s a commonly held view in Christians but it’s not supported by the Bible or the majority of biblical scholars. And for a few very good reasons.

a) Luke never states that. He never mentions Mary at all in his genealogy. On the contrary, he says it’s the genealogy of Jesus via Joseph. Apologists have tried to say “well what Luke meant to say was…” but that’s not what Luke actually says. Luke 3:23 says “Jesus, when he began his ministry, was about thirty years of age, being the son (as was supposed) of Joseph, the son of Heli…” There’s no mention of his mother or her bloodline.

b) Even if it were true, it wouldn’t help, because inheritance in Judaism comes down through the father’s bloodline, not the mother. Many Christians believe Mary and Joseph were cousins and somehow that means he was entitled to the kingship, but that’s just not how it worked in Judaism. Anyway, most biblical scholars tend to agree that both Matthew’s and Luke’s genealogies are fictional and were later additions to the Jesus story.

c) If Jesus was in any way entitled to hold the title of the King of the Jews, the Jews would acknowledge that. Even if they don’t consider him to be the messiah, that’s no reason to reject a legitimate heir to the throne. But no Jewish scholar, neither then nor now, considers him to have been the king of the Jews.

As for the NT, the two genealogies of Jesus are examples of the tendency towards the historification of traditional motifs in the gospel tradition. This means that the NT genealogies do not come from the earliest strata of the gospel tradition, as can be shown from the relation of the titles Son of God and Son of David in Rom. 1: 3-4 and Matt. I, respectively. Moreover, the contradictions between Matt. I and Luke 3 make impossible the belief that both genealogies are the result of accurate genealogical records; and the use of the genealogical Gattung in Judaism renders it highly improbable that either list preserves the family records of Joseph. Both of the lists fall into the category of Midrash, which has a homiletical and hortatory function, and thus may be considered part and parcel of the tendency towards historification of ‘non-historical’ materials. 1 But, in spite of the relative lateness of the genealogies in the gospel tradition, it is clear that they do not arise out of the Hellenistic church.

Marshall D. Johnson The Purpose of the Biblical Genealogies with Special Reference to the Setting of the Genealogies of Jesus

Nowhere is it so clear as in these two genealogies that theological metaphor and symbolic parable rather than actual history and factual information create and dominate the Christmas stories of the conception and infancy of Jesus.

Matthew’s list descends from David through Solomon (a king), but Luke’s descends from David through Nathan (a prophet). The other is that Matthew names Jesus’s grandfather as Jacob, but Luke names him as Heli. Any attempt at reconciling those versions for historical accuracy is love’s labor lost. They are parabolic lists, not historical records, and we return below to consider their separate purposes.

The First Christmas, Marcus Borg & Dominic Crossan

While Luke’s list may be less classically monarchical than Matthew’s, there is little likelihood that either is strictly historical.

Raymond E. Brown, An Introduction to the New Testament

Even such a routine item as Jesus’ genealogy is molded differently in terms of each Gospel’s purpose.

Edgar V. McKnight, Jesus Christ in History and Scripture

Unquestionably biased toward men, biblical laws of inheritance were not intended to hurt women, but to guarantee each tribe’s territorial integrity. When the Israelites entered Canaan, the land was divided among the twelve tribes and property passed from fathers to sons.

Joseph Telushkin, Biblical Literacy

There are other things in Jewish law that principally follow the paternal line—tribal rights, inheritance, and more.

9. "The Jews killed Jesus, not the Romans."

This is the anti-semitic view put forward by the Gospels (especially in Matthew), but it isn’t historical. For one thing, only Romans could have prisoners crucified in Judaea at the time of Jesus. If he was executed, it was done by order of Pontius Pilate and carried out by Roman soldiers. As for the idea that the Jews forced Pilate to execute Jesus, from the little we know Pontius Pilate from non-biblical sources (mostly from the accounts of Philo of Alexandria who actually met Pilate), he was brutal and didn’t give a damn what the Jews thought or wanted. Which made him fairly typical for a Roman prelate or prefect. Jesus was killed, by the way, not because he upset the Pharisees, but because he claimed to be the King of the Jews. Judaea, at the time, didn’t have a king. They were a Roman province. Herod Antipas was never king. He was the tetrarch of Galilee and Perea (not Judaea), basically a client governor appointed by Rome. He had very little power as did the Sanhedrin.

10. "Constantine wasn’t an Arian."

According to the sources we have for Constantine’s life, which admittedly aren’t great, he was baptised on his death bead by Eusebius of Nicomedia, who was an Arian. This would suggest that Constantine was an Arian. Yes, I know he supervised the Council of Nicaea, where Arianism was banned, but that was a decade earlier. He later changed his mind and welcomed Arius back. And Constantine’s son and successor, Constantius, was definitely an Arian, which suggests he was continuing in the footsteps of his father.

By the criteria employed by Athanasius and his ecclesiastical allies, and it is an offense to history to pretend that his personal beliefs were orthodox in the later sense of that term.

Timothy David Barnes – Constantine – Dynasty, Religion and Power in the Later Roman Empire

The Arian party, cowed and defeated in 325, suddenly recovered its power two years later and proceeded to dislodge its main opponents from their sees. When Constantine died in 337, though the heresiarch was dead, Arius’ supporters enjoyed a supremacy in the eastern Church which appeared almost complete. The reversal can be explained by a significant change at court. Ossius of Corduba returned to Spain not long after Nicaea. ‘ Eusebius of Nicomedia soon replaced him as Constantine’s close and constant adviser on ecclesiastical matters – and Eusebius was the architect of his party’s triumph.

Constantine and Eusebius – Timothy David Barnes

Constantine himself leaned toward Arianism later in his reign, and his eventual successor, his son Constantius, was openly Arian.

Encyclopedia Brittanica

11. "The Catholic Church wasn’t even around in the time of Theodosius."

Let me quote from Eusebius’s Church History, written in the early 300s:

“…let [these places] be confiscated and handed over incontestably and without delay to the Catholic church, and let other sites become public property.”

“The best thing would be for as many as are concerned for true and pure religion to come to the Catholic Church…”

The church of God which dwells in Philomelium, and to all the parishes of the holy Catholic Church in every place”

Also from Eusebius’ Life Of Constantine:

“The parts of the common body were united together and joined in a single harmony, and alone the Catholic Church of God shone forth gathered into itself…”

12. “There’s no such thing as a consensus or majority view of biblical scholars on this subject.”

I hear this a lot when I point out that this film tries to explain the consensus view of biblical scholarship. If you doubt that there is a consensus view on any particular topic, I invite you to open up Google and ask it “what is the view of the majority of biblical scholars on the subject of x”. And see what you discover.

Of course, the same Christians who try to make this argument, will also tell you that the majority of biblical scholars believe Jesus actually existed.

13. "Constantine didn’t suppress other Christian factions."

For good measure, Constantine issued a threatening letter addressed to every other group of heretics and schismatics known to him. It has been preserved by Eusebius (VC III. 63-6): Be it known to you by this present decree, you Novatians, Valentinians, Marcionites, Paulians and those called Cataphrygians, all in short who constitute the heresies by your private assemblies, how many are the falsehoods in which your idle folly is entangled and how venomous the poisons with which your teaching is involved, so that the healthy are brought to sickness and the living to everlasting death through you … Accordingly, since it is no longer possible to tolerate the pernicious effect of your destructiveness, by this decree we publicly command that none of you henceforth shall dare to assemble. Therefore, we have also given order that all your buildings are to be confiscated, the purport of this extending so far as to prohibit the gathering of assemblies of your superstitious folly not only in public but also in the houses of individuals or other private places … let [these places] be confiscated and handed over incontestably and without delay to the Catholic church, and let other sites become public property.

Constantine, Paul Stephenson

14." Jesus / Paul / The Gospels never said the end of the world would happen in their lifetime."

Paul:

“According to the Lord’s word, we tell you that we who are still alive, who are left until the coming of the Lord, will certainly not precede those who have fallen asleep. For the Lord himself will come down from heaven, with a loud command, with the voice of the archangel and with the trumpet call of God, and the dead in Christ will rise first. After that, we who are still alive and are left will be caught up together with them in the clouds to meet the Lord in the air. And so we will be with the Lord forever. Therefore encourage one another with these words.”

1 Thess 4:15-18

“Truly I say to you, this generation will not pass away until all these things take place.”

Matthew 24:34; Mark 13:30; and Luke 21:32.

Christianity began as an apocalyptic movement of a specifically nondoctrinal sort. The earliest believers in Jesus were believers in a message of eschatological judgment…

Like other Jews of his generation, Jesus of Nazareth seems to have believed that history was moving toward catastrophe, toward a “Day of the Lord” when men would be called upon to answer for their sins.

Celsus – On the True Doctrine (A Discourse Against the Christians) – R. Joseph Hoffman

“Paul (along with other apostles) taught that Jesus was soon to return from heaven in judgment on the earth. The coming end of all things was a source of continuous fascination for early Christians, who by and large expected that God would soon intervene in the affairs of the world to overthrow the forces of evil and establish his good kingdom, with Jesus at its head, here on earth. ”

Bart D. Ehrman. “Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why.”

Most biblical scholars today agree that early Christianity was eschatological and that this came from the teachings of Jesus.

No Gospel makes so much as does Matthew of the expectation that the visible Return of Christ will be within the lifetime of those who saw and heard Him.

B. H. Streeter, Four Gospels

The Matthean mission charge, which is a mixture of Marcan, Q and unique material, has always caused exegetical problems. On the one hand, since it confines the mission of the disciples to the Jews of Palestine (verses 5-6), it seems to contradict the command to make disciples of all nations at the conclusion of the gospel (28:19). On the other hand, it contains a prophecy that the Son of Man will come before they have completed the mission (10:23b), a prophecy which clearly did not come true during the lifetime of the historical disciples to whom this promise is made. Matthew’s arrangement of this material also causes problems in so far as he transposes verses 17-22 from the Marcan apocalyptic discourse (Mark 13:9, 11-13) for reasons which are disputed.

“Apocalyptic Eschatology in the Gospel of Matthew”, David C Sim

Similarly when he examines the teaching of the early Church, Dunn points to the resurrection of Jesus, the belief in his imminent return and the hope of a renewed community centred on Jerusalem as signs of apocalyptic influence….What Dunn has indicated is the way in which eschatology dominated early Christian theology. Most of the ideas he collects point to early Christianity as an eschatologically-orientated community, whose expectation about the future is distinguished, not so much by the so called ‘apocalyptic’ elements, but by the earnest conviction that the hopes of Judaism were already in the process of being realized.

“Open Heaven” – Study of the Apocalyptic in Judaism and Early Christianity, Christopher Rowland

15. "John’s Gospel is an eyewitness account."

The consensus of biblical scholarship is that none of the gospels are eyewitness accounts. The first one written was probably Mark, around 70CE, followed by Matthew and Luke, written 80-90 CE, and both of them copy large chunks from Mark, and either the Q Source or each other. Mark is obviously not an eyewitness (even if you believe that the author was “Mark”, a later companion of Peter, which most scholars do not), so why would eyewitnesses copy the work of someone who wasn’t? Which rules out Matthew and Luke. John, on the other hand, is very different.

The Gospel of John is so different from the Synoptics that most scholars conclude that it is fundamentally not a portrait of the historical Jesus but a profound meditation on his theological significance.

Understanding The Bible, Stephen Harris

“Reasons for frequent rejection of apostolic authorship

1. It is odd that the author, if he was the apostle John, should describe himself as ‘the disciple whom Jesus loved’

2. Much of what is found in the Synoptic Gospels is missing from the Gospel of John, which belies the fact that its author was one of the Twelve

3. As a Galilean fisherman, John would have been uneducated, possibly illiterate, and not sophisticated enough to produce this Gospel

4. A Galilean fisherman would not have been sufficiently well known in Jerusalem and to the family of the high priest to gain access to his courtyard and feel secure there when Jesus was on trial (18:15-16).

5. The Synoptic Gospels say that all the disciples forsook Jesus and fled when he was arrested, but the Gospel of John says that the beloved disciple, identified as John, followed him to the high priest’s courtyard and later stood by him at the cross.

6. The author of this Gospel shows an intimate knowledge of the geography of Jerusalem and Judea, something one would not expect from John who was a Galilean

The most recent studies of authorship continue to reflect differences of opinion.”

John, Colin G. Kruse

16. "Theodosius didn't oppress non-Christian religions."

Theodosian decrees were a series of laws issued by the Roman Emperor Theodosius I in the late 4th century AD. The laws were aimed at suppressing paganism and promoting Christianity. Between 389 and 391 he issued the “Theodosian decrees,” which established a practical ban on paganism; visits to the temples were forbidden, the remaining pagan holidays were abolished, the sacred fire in the Temple of Vesta in the Roman Forum was extinguished as the Vestal Virgins were disbanded, and auspices and witchcraft were deemed punishable offenses.

Torture and death weren’t stipulated in the “Theodosian decrees”, but the form of punishment was left open to “the will of Heaven”.

The edicts were a total persecution of paganism and non-Nicene forms of Christianity.

“They will suffer in the first place the chastisement of the divine condemnation and in the second the punishment of our authority which in accordance with the will of Heaven we shall decide to inflict.”

As Diarmin McCulloch wrote in his book “A History of Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years”:

“For most of its existence, Christianity has been the most intolerant of world faiths, doing its best to eliminate all competitors, with Judaism a qualified exception, for which (thanks to some thoughts from Augustine of Hippo) it found space to serve its own theological and social purposes.”

17. "Paul's teaching wasn't criticised by anyone."

We know that isn’t true from Paul’s own epistles, where he complains about “super-apostles” warning his communities that he was leading them astray. And we also know from his own epistles that he had serious disagreements with Peter and James. We can assume that at some point they also sent letters to Christian communities warning them about Paul, but those letters haven’t survived, falling victim to either lack of care by early Christians or deliberate destruction by Paul’s communities.

We also know that at least one early Christian community had serious disagreements with Paul.

The Ebionites.

“They use the Gospel according to Matthew only and repudiate the apostle Paul, saying that he was an apostate from the Law.”

“Paul and the Second Century”, Michael F. Bird (editor), Joseph R. Dodson (editor)

Those who are called Ebonites, then, agree that the world was made by God; but their opinions about the Lord are similar to those of Cerinthus and Carpocrates. They use the gospel according to Matthew only and repudiate the apostle Paul, saying that he was an apostate from the Law. As to the prophetical writings, they do their best to expound them diligently; they practice circumcision, persevere in the customs which are according to the Law, and practice a Jewish way of life, even adoring Jerusalem as if it were the house of God.

“Prescription against Heretics”, Tertullian

The Ebionites rejected the Pauline Epistles, and according to Origen they viewed Paul as an “apostate from the law”. The Ebionites may have been spiritual and physical descendants of the “super-apostles” — talented and respected Jewish Christian ministers in favour of mandatory circumcision of converts — who sought to undermine Paul in Galatia and Corinth. Epiphanius relates that the Ebionites opposed Paul, who they saw as responsible for the idea that Gentile Christians did not have to be circumcised or follow the Law of Moses, and named him an apostate. Epiphanius further relates that some Ebionites alleged that Paul was a Greek who converted to Judaism in order to marry the daughter of a high priest of Israel, but apostatized when she rejected him.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ebionites

18. "There was no debate about which books ended up in the NT."

“The decisions about which books should finally be considered canonical were not automatic or problem-free; the debates were long and drawn out, and sometimes harsh. Many Christians today may think that the canon of the New Testament simply appeared on the scene one day, soon after the death of Jesus, but nothing could be farther from the truth. As it turns out, we are able to pinpoint the first time that any Christian of record listed the twenty-seven books of our New Testament as the books of the New Testament— neither more nor fewer. Surprising as it may seem, this Christian was writing in the second half of the fourth century, nearly three hundred years after the books of the New Testament had themselves been written. The author was the powerful bishop of Alexandria named Athanasius. In the year 367 C.E., Athanasius wrote his annual pastoral letter to the Egyptian churches under his jurisdiction, and in it he included advice concerning which books should be read as scripture in the churches. He lists our twenty-seven books, excluding all others.”

Bart D. Ehrman, “Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why”

19. "The suggestion that the Jews were expecting the Messiah to rule the world is anti-Semitic."

Rejoice greatly, O daughter of Zion; shout, O daughter of Jerusalem: behold, thy King cometh unto thee: he is just, and having salvation; lowly, and riding upon an ass, and upon a colt the foal of an ass.

And he shall speak peace unto the heathen: and his dominion shall be from sea even to sea, and from the river even to the ends of the earth.

Zechariah 9:10.

12 This is the plague with which the Lord will strike all the nations that fought against Jerusalem: Their flesh will rot while they are still standing on their feet, their eyes will rot in their sockets, and their tongues will rot in their mouths. 13 On that day people will be stricken by the Lord with great panic. They will seize each other by the hand and attack one another. 14 Judah too will fight at Jerusalem. The wealth of all the surrounding nations will be collected—great quantities of gold and silver and clothing. 15 A similar plague will strike the horses and mules, the camels and donkeys, and all the animals in those camps.

16 Then the survivors from all the nations that have attacked Jerusalem will go up year after year to worship the King, the Lord Almighty, and to celebrate the Festival of Tabernacles. 17 If any of the peoples of the earth do not go up to Jerusalem to worship the King, the Lord Almighty, they will have no rain. 18 If the Egyptian people do not go up and take part, they will have no rain. The Lord[b] will bring on them the plague he inflicts on the nations that do not go up to celebrate the Festival of Tabernacles. 19 This will be the punishment of Egypt and the punishment of all the nations that do not go up to celebrate the Festival of Tabernacles.

Zechariah 14:12-19

20. "Jesus fulfilled the prophecies of the Jewish Messiah."

Jewish tradition affirms at least five things about the Messiah. He will: be a descendant of King David, gain sovereignty over the land of Israel, gather the Jews there from the four corners of the earth, restore them to full observance of Torah law, and, as a grand finale, bring peace to the whole world.

The most basic reason for the Jewish denial of the messianic claims made on Jesus’ behalf is that he did not usher in world peace, as Isaiah had prophesied: “And nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war anymore” (Isaiah 2:4). In addition, Jesus did not help bring about Jewish political sovereignty for the Jews or protection from their enemies.

Jewish Literacy – Joseph Telushkin

21. "The Christian factions that were outlawed were heretics."

The problems Christians faced were not confined to external threats of persecution. From the earliest times, Christians were aware that a variety of interpretations of the “truth” of the religion existed within their own ranks. Already the apostle Paul rails against “false teachers”— for example, in his letter to the Galatians. Reading the surviving accounts, we can see clearly that these opponents were not outsiders. They were Christians who understood the religion in fundamentally different ways. To deal with this problem, Christian leaders began to write tractates that opposed “heretics” (those who chose the wrong way to understand the faith); in a sense, some of Paul’s letters are the earliest representations of this kind of tractate. Eventually, though, Christians of all persuasions became involved in trying to establish the “true teaching” (the literal meaning of “orthodoxy”) and to oppose those who advocated false teaching. These anti-heretical tractates became an important feature of the landscape of early Christian literature. What is interesting is that even groups of “false teachers” wrote tractates against “false teachers,” so that the group that established once and for all what Christians were to believe (those responsible, for example, for the creeds that have come down to us today) are sometimes polemicized against by Christians who take the positions eventually decreed as false. This we have learned by relatively recent discoveries of “heretical” literature, in which the so-called heretics maintain that their views are correct and those of the “orthodox” church leaders are false.

Bart D. Ehrman. “Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why.”

22. "Luke was a great historian and Luke/Acts is historically reliable."

“The denunciation of Luke as a falsifier of history, at best naive, is forceful and scathing.”

“Franz Overbeck… in 1919 referred to the work of Luke as a ‘gaffe on the scale of world history’”

“Frequently the historians of early Christianity begin by questioning the historical value of Acts”

The First Christian Historian: Writing the ‘Acts of the Apostles’, Daniel Marguerat

“The Book of Acts is an idealized narrative of Christian beginnings”

“More significant, although Paul is Luke’s heroic exemplar of true Christianity, the author does not actually portray Paul as he reveals himself in his letters, omitting controversial Pauline ideas and even contradicting some of Paul’s own versions of events.”

Stephen Harris – Understanding the Bible

“The Luke Gospel is also historically unreliable. There’s no evidence of a Roman census around the birth of Jesus and his claims about Quirinius are inconsistent with Tacitus, etc. “

The New Oxford Annotated Bible

James Dunn points out some of the problems with Acts:

• a degree of idealization or romanticization of the first Jerusalem community (Acts 2.41-47: 4.32-35)

• his practice of telescoping events;

• his playing down the probable seriousness of the crisis for the Jerusalem church occasioned by the activities of the Hellenists and Stephen in particular (chs. 6-8)

• his smoothing out initial relations between Paul and the Jerusalem church (9.23-30)

• his ignoring the confrontations between Paul and other Christian Jews al Antioch (Gal. 2. 11-16) and Galatia (Galatians)

• his failure to mention Paul’s letter-writing activity and the tensions they indicate, particularly in Paul’s relations with the church in Corinth (2 Cor. 2.12-13: 7.5-7);

• his side-lining of the principal reason why Paul made his final journey to Jerusalem do deliver the collection)

James D. G. Dunn – Beginning from Jerusalem

23. "Isaiah predicted the virgin birth"

Many Chrisitans are convinced that Isaiah predicted Jesus, but Jewish scholars (who, you would think, are the experts on understanding their own prophets and scriptures) have other ideas. And these ideas about who and what Isaiah was talking about pre-date Christianity. Keep in mind that we know Matthew, the first gospel writer to mention Jesus’ birth, had a (badly translated) copy of Isaiah in front of him while he was writing it (see below for how we know that), so it seems he tried to write his Jesus story to fit the prophecies as understood them. There’s really no other way to explain the virgin birth story. As we said in the documentary, he based the virgin idea on a bad translation of Isaiah contained in the Septuagint that he was using. So if you’re thinking “but Jesus fits the prophecy so well!”, well yeah, that’s because Matthew deliberately wrote it that way.

Also, most Christians don’t read all of Isaiah. If they did, it would be quite clear that Isaiah was talking about contemporary issues in his time, not about some child who would be born 700 years later. That makes absolutely zero sense.

“the Heb word “ʿalmah” simply means young woman, not virgin”

The Oxford Annotated Bible

The Hebrew word עַלְמָה ‘almāh translates into English as “young woman,” although it is translated in the Koine Greek Septuagint as παρθένος parthenos, meaning virgin, and was subsequently picked up by the gospels of Matthew and Luke and used as a messianic prophecy;

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isaiah_7:14

For several reasons, Jews have never understood this passage as meaning what fundamentalist Christians claim it does. First, and most important, almak, which Christians have usually translated as “virgin,” actually means “young woman.” The Hebrew word for virgin is betulah. While a young woman may also be a virgin, if Isaiah intended to prophesy the miracle of a virgin giving birth, would he not, if for no other reason than to avoid ambiguity, have used the word betulah, since it has no meaning other than virgin?* *See, for example, Leviticus 21:3; Deuteronomy 22:19, 28, and Ezekiel 44:22.

Second, the prophecy’s context makes it clear that God was sending a sign to King Ahaz, and was not speaking of a child who would be born more than seven centuries later (would you be convinced by a prophetic sign given in 2005 CE. that would be fulfilled in 2705?). Thus, Isaiah tells Ahaz that “the young woman,” not “a young woman,” shall conceive, thus implying that he is alluding to a young woman known to the king. Probably, Isaiah is referring to Ahaz’s young bride, the queen, and to a son who will be granted the couple as a kind of replacement for the little princes Ahaz had earlier sacrificed (II Chronicles 28:3). While one is free to question the justice of giving an infant to a man guilty of such horrific child abuse, Hezekiah, the child who shortly thereafter is born to the queen, is, unlike his father, loyal to the traditions of David (see entry 98). Many Christians have also attached christological significance to Isaiah 53, which speaks of the “suffering servant of God.” Christian exegetes have often interpreted this chapter as prophesying the mission of Jesus, whom they deem to be both a prophet and God, and whom they believe came to this earth to suffer a torturous, sacrificial death. While it is true that Isaiah speaks of a suffering and despised “servant of God,” the contention that he is speaking about Jesus is without foundation. “Servant of God” either refers to Isaiah himself, who like most of the prophets suffered for his service to the Lord, or to the collective Jewish people, who are referred to by the term “servant of God” nine times in earlier chapters of Isaiah (41:8,9; 44:1, 2, 21, 26; 45:4; 48:20; 49:3). Traditional Jewish theology has generally understood chapter 53 as referring to the Jewish people’s sufferings while trying to maintain their faith and make the idea of One God known to the world.

Jewish Literacy – Rabbi Joseph Telushkin

24. "There were no early Christian critics."

Although the works of many early critics of the Church were burned by Christian emperors or were otherwise destroyed in the second and third centuries, the major work of the Greek philosopher, Celsus, is an exception. His polemical attack on the beliefs and practices of Christianity, On the True Doctrine, written around 178 A.D., is one of the earliest surviving documents of its kind. Christianity was born of controversy. Not only the twenty-seven-book canon of writings but the individual books of the New Testament itself are charged with the spirit of contention and defense – so much, indeed, that a strong case may be made for seeing the canon as the earliest stratum in Christian apologetic literature. ‘ Paul’s own letters to wayward communities of Christian believers as far removed as Rome and Laodicaea suggest that the developing churches, themselves spewed into existence by the expulsion of heretical “Nazarenes” from the synagogues of Palestine, were called upon from an early date to defend themselves against Jewish and Greek detractors who made a mockery of the new, and to all seeming, eccentric messianic faith. As understood by the outsiders–Jew and Greek alike–the preaching of the Christian missionaries, centering on the humiliation and execution of a little- known Galilean rabbi, was either insanity or mere non- sense (I Cor. 1.23). The very situation of the Christians in society, their perceived illegitimacy and the harassment that followed from that perception, was a persuasive case against the merit of the claims they advanced on behalf of their Christ; yet they boasted of a continuity between his fate and their own rejection, and interpreted the syzygy with growing conviction as God’s judgment on the “wisdom” of men (I Cor. 1.20f.). Only to “those who are perishing,” Paul as- sured his converts, did the message seem foolish. “To those of us who are saved, it is nothing less than the power of God’ (I Cor. 1.18).

Celsus – On the True Doctrine (A Discourse Against the Christians) – R. Joseph Hoffman

25. "The ending of Mark's gospel contains the resurrection appearances."

“Mark 16:9-20 This ending was probably added sometime in the mid-second century CE to bring Mark’s ending into conformity with the postresurrection accounts found in Matthew, Luke and John.”

Oxford Annotated Bible

“As I’m sure you already know, the two oldest manuscripts of Mark 16 (from the 300s) conclude with verse 8.

They were added to Mark by a later scribe and then recopied over the years. This is a fabricated story that has been put into the Bible by a copyist who falsified the text.”

Forged, Bart D. Ehrman

“[The earliest manuscripts and some other ancient witnesses do not have verses 9–20.]”

Holy Bible (NIV)

“It is virtually certain that 16:9-20 is a later addition and not the original ending of the Gospel of Mark.”

The Gospel according to Mark, James R. Edwards Jr.

Once upon a time, there was a scholarly consensus that the ending of Mark’s Gospel in our earliest manuscripts, at 16:8, was the result of the accidental truncation or deliberate mutilation of a story that originally continued beyond that point. Today, the consensus has shifted, and the majority of commentators appear to regard 16:8 as the intended conclusion to the Gospel.

James F. McGrath

Early Christian writers, such as Eusebius of Caesarea and Jerome, note that the longer ending was not included in some of the earliest manuscripts of Mark’s Gospel that they had seen.

26. "The Epistles of Peter and James are authentic."

“The book was almost certainly not actually written by Jesus’s disciple Peter.”

Bart D. Ehrman, Forged: Writing in the Name of God—Why the Bible’s Authors Are Not Who We Think They Are”, talking about 1 Peter.

“This should come as no surprise, really. As it turns out, there is New Testament evidence about Peter’s education level. According to Acts 4:13, both Peter and his companion John, also a fisherman, were agrammatoi, a Greek word that literally means “unlettered,” that is, “illiterate.” And so, is it possible that Peter wrote 1 and 2 Peter? We have seen good reasons for believing he did not write 2 Peter, and some reason for thinking he didn’t write 1 Peter. But it is highly probable that in fact he could not write at all. I should point out that the book of 1 Peter is written by a highly literate, highly educated, Greek-speaking Christian who is intimately familiar with the Jewish Scriptures in their Greek translation, the Septuagint. This is not Peter. It is theoretically possible, of course, that Peter decided to go to school after Jesus’s resurrection. In this imaginative (not to say imaginary) scenario, he learned his alphabet, learned how to sound out syllables and then words, learned to read, and learned to write. Then he took Greek classes, mastered Greek as a foreign language, and started memorizing large chunks of the Septuagint, after which he took Greek composition classes and learned how to compose complicated and rhetorically effective sentences; then, toward the end of his life, he wrote 1 Peter. Is this scenario plausible? Apart from the fact that we don’t know of “adult education” classes in antiquity there’s no evidence they existed I think most reasonable people would conclude that Peter probably had other things on his mind and on his hands after he came to believe that Jesus was raised from the dead. He probably never thought for a single second about learning how to become a rhetorically skilled Greek author. Some scholars have suggested that Peter did not directly write 1 Peter (as I’ve indicated, almost no one thinks he wrote 2 Peter), but that he indirectly wrote it, for example, by dictating the letter to a scribe. Some have noted that the letter is written “through Silvanus” (5:12) and thought that maybe Silvanus wrote down Peter’s thoughts for him. I deal with this question of whether scribes or secretaries actually ever composed such letter-essays in Chapter 4. The answer is, “Almost certainly not.” But for now I can say at least a couple of words about the case of 1 Peter. “

Bart D. Ehrman, Forged.

“The majority of scholars agree that 1 Peter, like James and the pastoral epistles, is pseudonymous, the work of a later Christian writing in Peter’s name. This consensus is based on several factors, ranging from the elegant Greek style in which the epistle is composed to the particular social circumstances it describes. “

Stephen Harris – Understanding the Bible

“Although relatively late church traditions ascribe this epistle to James, whom Paul called “the Lord’s brother” (Gal. 1:19), most scholars question this claim. “

Stephen Harris – Understanding the Bible

“Thus most scholars interpret the document as a letter from the last decade of the first century CE, written in Peter’s name to support the claim that its teaching represented the apostolic faith.”

The New Oxford Annotated Bible

27. "Constantine wasn't the head of the church."

“The Romans took this over from the Greeks, and called those who held their highest rank of priesthood pontifices, and legislated that kings should be numbered among them because of their important rank. All the kings after Numa Pompilius (who was the first to do so) and all the Roman emperors from Octavian have held this office: as soon as each assumed supreme power, the priestly robes were brought to him by the pontifices and he was styled pontifex maximus (chief priest). All the earlier emperors seem to have been very pleased to accept the honour and to use this title, even Constantine who, when he came to the throne, was perverted religiously and embraced the Christian faith and all his successors, including Valentinian and Valens.”

Zosimus, a Greek historian who lived in Constantinople, writing 498–518

“According to Zosimus, Constantine himself, in the year 325, assumed the title of Pontifex Maximus, which the heathen emperors before him had appropriated, because it contributed to exalt at once the imperial and episcopal dignity, and served to justify the interference of the emperor in ecclesiastical councils and in the nomination of bishops. Constantine’s successors followed his example until the days of Gratian, who was the last emperor to whom the title was applied. Some scholars doubt Zosimus’s assertion, notwithstanding the fact that the medals of Constantine and his successors, down to Gratian, and the inscriptions relating to them, give them the title of Pontifex Maximus, on the ground that it may have been one of those traditional titles which the power of habit preserved, without any meaning being connected with them.”

The Cyclopedia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature, James Strong and John McClintock

28. "The interviews with the scholars in the film were edited to make it look like they were saying something they didn't intend to say."

I knew there would be some people who would suggest that, which is why I made all of the unedited interviews available on our USB – all 24 hours of them!

29. "If the stories in the gospels weren't true, someone would have said so at the time."

There are a couple of obvious problems with that argument.

The first is that the gospels were written well after the Jewish-Roman war, in which most of the original Christians in Jerusalem (ie the people who knew Jesus and the original apostles) were either killed or disappeated into exile.

The second problem is that the gospels and Paul’s epistles were writtten by and for people who weren’t living in or near Jerusalem. They were in various other parts of the Roman empire (Galatia, Corinth, Syria, Rome, etc) very far away from Jerusalem and Galilee. Nobody could get on the phone to an investigative journalist in Jerusalem to fact check the story.

The third problem is that any criticism of the story that might have been written by someone in Jerusalem wasn’t likely to survive the next 1000 years. Anybody who has studied the ancient world knows that very few scrolls and letters written in the first century CE have survived. They were typically written on vellum or parchment, neither of which survives very long. They would have to be copied by scribes many times over the last 2000 years to have survived. And once the Roman Empire became Christian, it was very unlikely that any such letter or scroll would have survived. We know from the surviving writings of the “Church Fathers” that there were plenty of critics of Christianity in the first few centuries, and plenty of disagreement inside Christianity, but very few of those writings have survived, except what we know of them from when they were quoted by the Church Fathers in order to refute them. It’s the same reason we don’t have any genuine writings from Peter or James or the other apostles. They must have existed. But, for reasons unknown, they didn’t survive and they aren’t even mentioned in the oldest sources we have.

30. "There's more evidence for Jesus than for Caesar / Alexander / anyone else in ancient history."

This is a commonly-held Christian belief, but it’s not even remotely true.

For a start, for both Caesar and Alexander (not to mention many other people from Caesar’s era), we have eyewitness and contemporaneous accounts.

For Julius Caesar, who died in 44 BCE, we have his own accounts of the Gallic Wars, the speeches of Cicero (an eyewitness), Sallust’s account of Catiline’s War (another eyewitness), Augustus’ Res Gestae Divi Augusti (Augustus was Caesar’s nephew and adopted son, another eyewitness), Suetonius’s section on Caesar in Twelve Caesars, and Plutarch’s section on Caesar in Plutarchs’s Lives. We also have coins from Caesar’s era with his name and face on them.

For Alexander, who died in 323 BCE, we have various sources of evidence, including contemporary accounts, later historical works, inscriptions, coins, and archaeological findings. In terms of contemporary evidence, we have the “Alexander Sarcophagus,” which contains an inscription referring to Alexander, and the Babylonian astronomical diary, which refers to Alexander’s invasion of Persia. We also have many coins with his name and face on them. The biographies we have written about him, eg the “Anabasis Alexandri” by Arrian, “The Life of Alexander” by Plutarch, “Historiae Alexandri Magni” by Quintus Curtius Rufus, and “Library of History” by Diodorus Siculus, were based on earlier texts by eyewitnesses and contemporaries, eg Alexander’s campaign historian Callisthenes, Alexander’s generals Ptolemy and Nearchus, Aristobulus, a junior officer on the campaigns, and Onesicritus, Alexander’s chief helmsman, and the account of Cleitarchus who, while not a direct witness of Alexander’s expedition, used sources which had just been published.

For Jesus we don’t have a single eyewitness or contemporaneous account.

We also know about many other contemporary accounts written about Caesar and Alexander which haven’t survived. It’s true that the writings about Jesus that have survived (eg the books of the NT) were written much sooner after his life than the biographies that have survived about Alexander (although it isn’t true for Caesar). The explanation for this, though, is that the Christians who ruled the Roman Empire from the 4th century onwards didn’t protect ancient writings (by making new copies of them) as they did the writings of early Christians. If they had bothered to protect these ancient scrolls, instead of letting them crumble into dust (or erase the ink on them and write over the top of them), we would still have way more eyewitness accounts of both Caesar and Alexander.

Unlike Caesar and Alexander, we know of no eyewitness or contemporary accounts written about Jesus. None of our sources mention anything specific. Nowhere in Paul’s epistles or the gospels does it say “according to the written account of Peter, who was there at the time…”. Yes, I know there are letters of Peter and James in the NT, and the gospel according to John, but scholars don’t consider them to be authentic (see points 15 and 26 in this FAQ).

The bottom line is that we have way more evidence for the lives of Caesar and Alexander than we do for Jesus. That’s just a fact.

31. "The author of the Gospel of Matthew was one of the disciples."

“Early in the history of the church, the view arose that the first Gospel in the canon was written by Matthew, one of the twelve apostles of Jesus and an eyewitness of his ministry. Most scholars doubt this tradition, primarily because the author relies on a number of earlier sources. This is true whether one accepts the two-document hypothesis or a more complex theory. It seems unlikely that an eyewitness of Jesus’ ministry, such as the apostle Matthew, would need to rely on others for information about it…. The Gospel itself makes no claims concerning who wrote it. Modern scholarship therefore has to leave the author anonymous.”

An introduction to the New Testament and the origins of Christianity – Delbert Burkett, chapter 12

“From the early second century the Gospel’s author was identified as Matthew, one of the twelve disciples…. If, however, the Evangelist’s main sources were the Gospel of Mark and Q, it is difficult to explain why one of the twelve disciples should be so heavily reliant on a Gospel that was thought to have been written by someone who was not one of Jesus’s disciples. Wouldn’t Matthew have had a rich store of experiences to draw upon? It is, of course, possible that some of the Gospel’s unique materials (M) do originate with Matthew, the disciple, but most scholars hold that the author/editor is someone other than the disciple Matthew (even if, as here, he is referred to as Matthew out of convenience).”

– The New Oxford Annotated Bible, page 1383

“Most scholars believe that Matthew’s Gospel is an expanded edition of Mark… “

Stephen Harris – Understanding the Bible, page 351

“Skepticism increased in the nineteenth century with the growing consensus that the Gospels were composite documents of uncertain authorship and had been written without the eyewitness authority of their sainted composers.”

Howard W. Clarke – The Gospel of Matthew and Its Readers – A Historical Introduction to the First Gospel

32. "The Jews did have a king during Jesus' lifetime."

As we state in the film, claiming to be the king of the Jews in Jesus’ lifetime would be considered an act of treason against Rome, because Judaea didn’t have a king during this period. They were occupied by Rome and considered a province of the Roman Empire. They therefore had an Emperor, Tiberius Caesar. The Romans likely crucified Jesus for the crime of lèse-majesté.

Some people seem to think that Herod Agrippa was the King of Judaea, but that’s incorrect. He was briefly king about a decade after Jesus died (41-44 CE), but in 6 CE, Judea came under direct Roman rule as the southern part of the province of Iudaea.

In the first century, Jews did not have a king. They were ruled by a foreign power, Rome, and many Jews considered this to be an awful and untenable situation of oppression. They were anticipating that God would once again raise up a Jewish king to overthrow the enemy and reestablish a sovereign state in Israel. This would be God’s powerful and exalted anointed one, the messiah.

Bart Ehrman, Why Paul Persecuted the Christians

33. "Paul was accepted by the apostles."

It’s evident from Paul’s own letters that his relationship with Peter and James was tense. There’s the infamous “Incident at Antioch“, his complaints about “super apostles” and “false teachers” going out to his communities warning them about Paul (probably sent by Peter or James, Galatians 1:6–9, 2 Corinthians 11:5; 12:11), and his suggestion, late in his life, that he wasn’t confident that the money he was collecting to take back to Jerusalem would be “favorably received” (Romans 15:31). In fact, it seems that he was arrested when he took the money back to Jerusalem.

Unfortunately, we have no authentic writings by Peter, James or any of the other original apostles and disciples (see point 26), to know what they actually thought about Paul and his teachings. We only have Acts, which is notoriously unreliable (see point 22) and an obvious attempt to try to whitewash the tensions between Paul and Peter, written by a member of Paul’s community as some kind of damage control.

We do, however, have the Pseudo-Clementines, which provide a different perspective. Regardless of how accurately they depict Peter’s actual views, they reflect the views of some members of the Christian community in the fourth century.

“The Pseudo-Clementines are two fourth-century writings that claim to be written by Clement of Rome…. The books are called the Pseudo-Clementines because Clement did not actually write them. They too are forgeries. And so the Letter allegedly by Peter to James is a forgery given in the manuscript tradition of another forgery.

In any event, the letter allegedly written by Peter to the brother of Jesus and the head of the church in Jerusalem, is found at the beginning of the Pseudo-Clementine Homilies. It is a short but interesting letter, that celebrates the importance for Christians to continue keeping the Jewish Law. The reason for Peter’s concern behind the letter is clear: there have been some Gentiles “who have rejected my lawful preaching [that is preaching about and in accordance with the Law], and have preferred a lawless and absurd doctrine of the man who is my enemy” (2.3). These Gentile enemies have tried to “distort my words by interpretations of many sorts as if I taught the dissolution of the Law” (2.4). But for Peter this is a heinous charge, for he would never oppose “the Law of God which was made known by Moses” and which was borne witness to by Jesus, who indicated that none of the Law will ever pass away while there is a heaven and earth (quoting Matt. 5:18). Peter, in other words, is in full support of the Mosaic Law, which continues in full force; to think otherwise is to oppose God, Moses, and Jesus (2.5). It is only “the man who is my enemy,” and the Gentiles he has influenced, who have twisted Peter’s words to make him appear to say otherwise.

No one thinks that the actual author of this short letter was Peter himself. But it was certainly someone who wanted his readers to think he was Peter. And the identity of his opponent is no mystery: it is Paul (“the man who is my enemy”) and his followers (“the Gentiles”).

This book provides the counter-view to that found in the New Testament book of Acts, where Paul and Peter are thought to be completely on the same side and simpatico on every major issue. Not according to this short letter. Here Peter and James are the heroes of the faith, and Paul is the great enemy.”

Bart Ehrman, Was Paul Peter’s Enemy?

“Already the apostle Paul rails against “false teachers”— for example, in his letter to the Galatians. Reading the surviving accounts, we can see clearly that these opponents were not outsiders. They were Christians who understood the religion in fundamentally different ways.”

Bart D. Ehrman. “Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why.”

“Luke’s portrayals of Peter and Paul might finally make sense as mythmaking instead of historiography.”

Burton L. Mack “The Christian Myth: Origins, Logic, and Legacy”

34. "There were no resurrected gods before Jesus."

According to Plutarch’s Moralia, Osiris rose from the dead to train his son, Horus: “Later, as they relate, Osiris came to Horus from the other world and exercised and trained him for the battle.” (source, Chapter 19, Verse 1)

Some Christians seem to have the opinion that, as Plutarch was writing around 100 CE, he copied the resurrected god motif from Christianity. But scholars agree that he was accurately depicting the beliefs of the ancient Egyptians.

“As historians of Roman religion have been impressed by the depth of knowledge reflected in Plutarch’s Quaestiones Romanae, so Egyptologists have often cited Plutarch’s de Iside as a relatively accurate account of the cultic practices associated with Isis in the Pharaonic period. Both Gwyn Griffiths and Hani felt that Plutarch, despite his inability to read hieroglyphics or to converse with non-Alexandrian natives, was a good religious historian.”

35. "Paul met the resurrected Jesus."

Paul actually never states that he met a bodily resurrection of Jesus.

In 1 Corinthians 15 he says “he appeared”, first to 500 brothers and sister and then to Paul. What does he mean by “appeared”?

According to Bart Ehrman, he meant he appeared as a spirit, not in the flesh:

When Paul thought Jesus was physically raised from the dead, that was NOT a contradiction to his claim that Jesus had a spiritual body at the resurrection. Spiritual bodies *were* physical. We too will be raised (for Paul) into spiritual bodies. At that time we will not have “flesh,” because sin will no longer have any role to play in our existence. But when he says this, he means it in the ancient, not the modern, sense.

Later Christian theologians who were NOT raised in Jewish apocalyptic thinking did not make this distinction that Paul made between body and flesh, leading to all sorts of confusions. They stressed the “resurrection of the flesh,” which for Paul would have been nonsense. For Paul, flesh and blood do not inherit the kingdom of God. They are done away with, because people are raised in spiritual bodies, just as Christ was. But later theologians (for example, Tertullian) did not make this distinction and stressed that it is precisely the “flesh” that comes to be raised. By that, he meant what Paul meant when he talked about “body.”

One of the ironies that was created is that later theologians stressed the resurrection of the flesh thinking that they were advocating Paul’s view, e.g., against Gnostics. In fact, they were not advocating Paul’s view at all, since Paul did not think the flesh would be raised.

Bart Ehrman, Did Paul Believe that the Fleshly Body Would be Resurrected

In Galatians 1:16, Paul says God “was pleased to reveal his Son in me”. Again, this doesn’t sound like he appeared to Paul in some kind of bodily form.

In 2 Corinthians 12:1-7, he says he had “revelations from the Lord”. This is also the chapter where he talks about being “caught up to the third heaven”, where he was told “inexpressible things, things that no one is permitted to tell”, which sounds like some kind of dream he had.

36. "Jesus didn't expect Gentiles to convert to Judaism."

There’s some confusion in the New Testament about Jesus’ views on the Gentiles. Paul obviously believed Gentiles didn’t need to convert to Judaism, yet Jesus’ apostles didn’t agree. That’s why they summoned him to Jerusalem for the “Council of Jerusalem”.

Acts says that “certain men which came down from Judaea” were preaching that “unless you are circumcised according to the custom of Moses, you cannot be saved”. While it doesn’t specifcy who these men are, it seems natural to assume that if they had enough authority to override Paul, then they were probably sent by Peter and/or James, especially as we know they were of the same opinion.

Then in Matthew we have Jesus at first saying “Go nowhere among the Gentiles, and enter no town of the Samaritans, but go rather to the lost sheep of the house of Israel” (Matt 10:5), but later his ghost/spirit appears to them and gives them “The Great Commission” outlined in Matthew 28:16–20. It also appears in the other gospels, but we know that in Mark 16:14–18, this ending is a later addition to the gospel, as it doesn’t appear in the oldest versions (see point #25).

So the question is – if Jesus ever actually said that Gentiles didn’t need to convert to Judaism in order to be saved, why didn’t Peter and James seem to be aware of it?

37. "Paul and the collection"

The collection is mentioned in 1 Cor 16:1-4, 2 Cor 8-9 and Rom 15:25-32.

1 Cor 16:1-4 mentions a “collection for the Lord’s people”

2 Cor 7 Paul is apparently defending himself against claims that he is doing something suspicious, perhaps related to the collection, as it appears the collection had stalled: “We have wronged no one, we have corrupted no one, we have exploited no one.”

This isn’t a controversial view. The New Oxford Annotated Bible, in its notes for 2 Cor 12:16 “Let it be assumed that I did not burden you. Nevertheless (you say) since I was crafty, I took you in by deceit.”, says “16: Deceit, Paul is accused of an unidentified deception related to money.”

In 2 Cor 8-9, Paul compares Corinth’s reluctance to share their money with the Macedonian churches and then tries to emotionally manipulate them into giving more, saying he wants to “test the sincerity of your love by comparing it with the earnestness of others” and telling them they should “finish the work”.

In Rom 15:25-32 Paul asks the Romans to “Pray that … the contribution I take to Jerusalem may be favorably received by the Lord’s people there…”

So it seems that Paul wasn’t sure how Jerusalem would react to his “gift”. Why would they not accept charity if they were poor or suffering under a famine, as the donation is usually positioned? That makes no sense.

Another interesting point is that Luke, who in the Book of Acts tries very hard to idealise the relationship between Paul and the Jerusalem church, and tries to edify Paul as much as possible, makes no mention of the collection or how it was received by the Jerusalem church. That’s a pretty interesting omission. If it had been well received, it seems certain Luke would have used it to strengthen Paul’s credentials. But he makes no mention of it, even though he writes as if he accompanied Paul on the journey (which most scholars don’t believe).

He simply says that, after being warned by several people not to go to Jerusalem, that Paul and his companions (supposedly including Luke) went to visit James (Acts 21:18), where Paul “reported in detail what God had done among the Gentiles through his ministry”. James then warns him that the Jews amongst the Jesus community in Jerusalem “are zealous for the law. They have been informed that you teach all the Jews who live among the Gentiles to turn away from Moses, telling them not to circumcise their children or live according to our customs.” Then he orders Paul to take four men he knows to the temple to make an offering.

Then Luke says that “some Jews from the province of Asia” had Paul arrested, saying “This is the man who teaches everyone everywhere against our people and our law and this place. And besides, he has brought Greeks into the temple and defiled this holy place.” Of course, Peter and James were Jews from the province of Asia (in Roman times, this included Judaea), so this could be referring to them or their followers.

So, in summary, Luke doesn’t mention the collection or how it was received, but says James orders Paul to go to the temple, where Paul is arrested. It sounds very much like Paul took the collection as a bribe to convince James to stop telling his churches that he was teaching a false gospel. It might also be true that the Jerusalem church was poor and suffering under a famine. This doesn’t negate the bribe aspect. Luke, it seems, didn’t find the offering sufficient, and set Paul up at the temple to have him arrested, thereby getting rid of someone who was, in his view, corrupting the teachings of his brother, Jesus.

The idea that Paul’s “collection” might have been some kind of “polite bribe” isn’t original. Scholars have been aware of this for a long time.

One of the important questions raised by Galatians 2.10 is whether this stipulation was some sort of qualification to the agreement of Galatians 2.7-9. The question can be posed more precisely: did any or all of the Jerusalem leadership regard this codicil to the agreement as some sort of concession which safeguarded the more traditional Jewish view of covenant obligation — the giving of alms being regarded as a crucially important expression of covenant-obligated ‘righteousness’? If the answer is in the affirmative, that would give the subsequent collection a considerable significance. For in making the collection, Paul would then be acting in a way that recognized or even agreed with the Jerusalem leadership’s concern to maintain at least some element of ‘covenantal nomism’: that non-Jews’ acceptance of the gospel must (also) be evidenced by alms-giving.

More disturbing is the implication of his request to the Romans to pray ‘that my service for Jerusalem might be acceptable (euprosdektos) lo the saints’ (15.31 ). Paul evidently had some foreboding, as well he might, that the collection would not prove ‘acceptable’ to the saints in Jerusalem!

The collection was clearly Paul’s attempt lo heal the breach with the mother congregations in regard to the wider Mediterranean mission, to restore the fractured koinonia of Jews and Gentiles.

Should the collection, then, be seen as a direct implementation of the codicil added to the Jerusalem agreement in Gal. 2.10? No doubt it was so viewed by some. Paul himself must have been aware of this possible interpretation of the action and may well have been willing for it to be so interpreted, in the hope that it might facilitate rapprochement with Jerusalem. Indeed, his exposition of the obligation laid upon believers, Corinthian Gentiles specifically, in terms of ‘good works’, ‘submission’ and ‘righteousness’, suggests that Paul was quite ready to encourage such an interpretation.

James D. G. Dunn – Beginning From Jerusalem

“I have coined the phrase that the collection was “a polite bribe” on Paul’s part.”

Gerd Lüdemannm Paul: The Founder of Christianity

Emeritus Professor of the History and Literature of Early Christianity

Georg-August-University of Göttingen

38. "Jesus never said he was God."

“I and the Father are one.” (John 10:30)

“His Jewish opponents picked up stones to stone him” (John 10:31). Why? “For blasphemy, because you, a mere man, claim to be God” (John 10:33).

“Very truly I tell you, … before Abraham was born, I am!”(John 8:58), quoting the great “I AM” of Exodus 3:14.

It is true that Jesus never said the exact words, “I am God.” He did, however, make the claim to be God in many different ways, and

those who heard Him knew exactly what He was saying. …. Did Jesus say He was God? Yes, in many ways, including applying the names and attributes of God to Himself. He made it clear that He was God incarnate, proving it by His words, by His miracles, and finally by His resurrection from the dead. (gotquestions.org)

39. "Jesus believed / said he was God."

In “How Jesus Became God: The Exaltation of a Jewish Preacher From Galilee”, Bart Ehrman talks about the claims made in the John gospel, which is usually considered by scholars to be the last one composed, where Jesus sounds like he’s saying he and God are one and the same, eg “Truly I tell you, before Abraham was, I am”. But then Bart writes:

“As I pointed out, we have numerous earlier sources for the historical Jesus: a few comments in Paul (including several quotations from Jesus’s teachings), Mark, Q, M, and L, not to mention the finished Gospels of Matthew and Luke. In none of them do we find exalted claims of this sort. If Jesus went around Galilee proclaiming himself to be a divine being sent from God—one who existed before the creation of the world, who was in fact equal with God—could anything else that he might say be so breathtaking and thunderously important? And yet none of these earlier sources says any such thing about him.”

40. "The name "Jesus" doesn't mean "messiah" or "saviour"."

The word Jesus is the Latin form of the Greek Iesous, which in turn is the transliteration of the Hebrew Jeshua, or Joshua, or again Jehoshua, meaning “Jehovah is salvation”, ie Jehovah is the “saviour”.

Messiah, (from Hebrew mashiaḥ, “anointed”), in Judaism, the expected king of the Davidic line who would deliver Israel from foreign bondage and restore the glories of its golden age, ie a “saviour”.

41. Jesus preached against Torah

“Do not think that I came to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I did not come to abolish but to fulfill” (Matt 5:17).